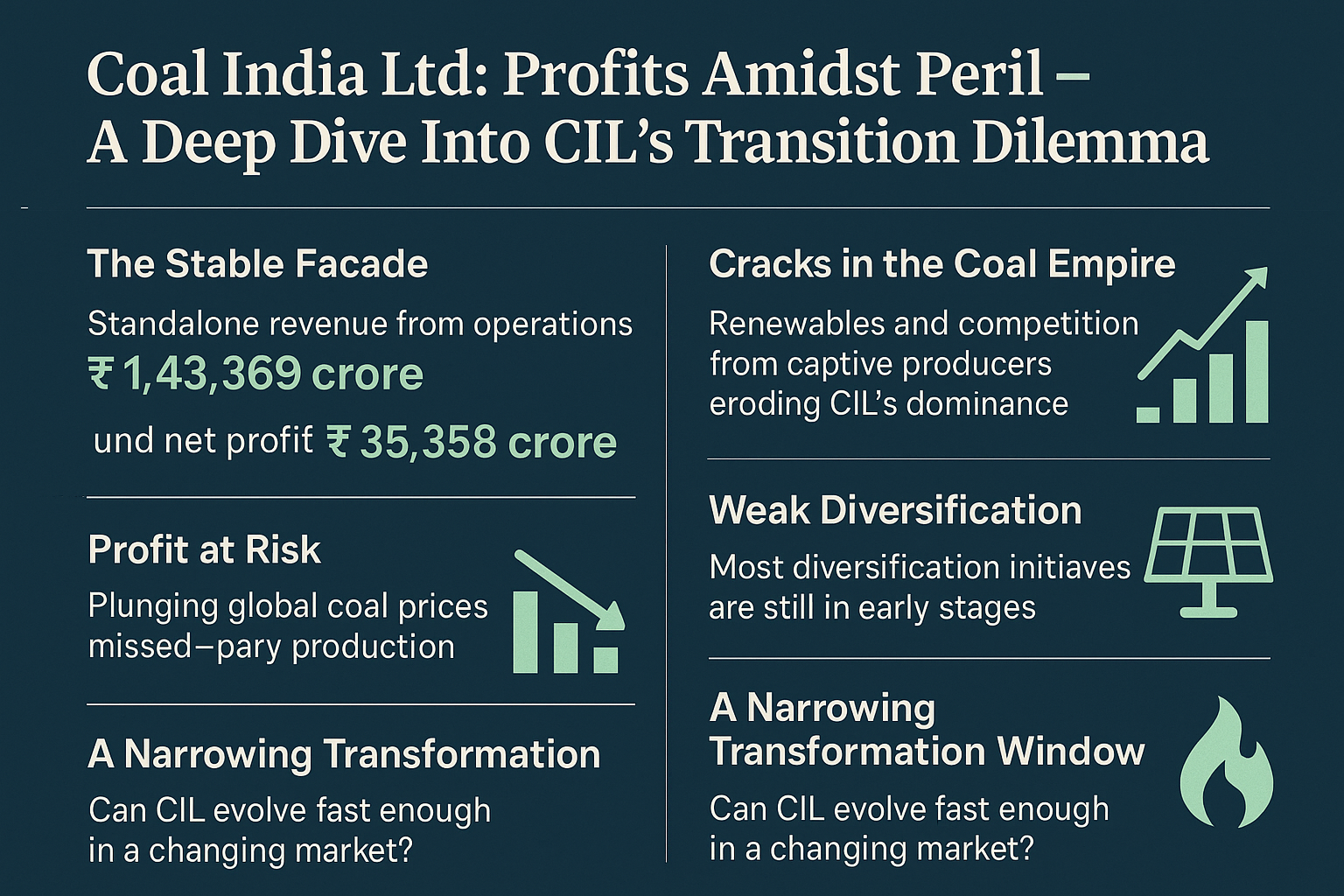

India’s largest coal producer, Coal India Ltd (CIL), recently released its audited financials for FY25, posting robust figures that on the surface reflect a picture of corporate stability. The company recorded a revenue from operations of ₹1,43,369 crore and a net profit of ₹35,358 crore, enabling a final dividend of ₹5.15 per share, following an earlier interim payout of ₹15.75.

But while the headline numbers impress, they mask a more complex and turbulent reality for CIL—one fraught with structural headwinds, strategic uncertainties, and mounting existential challenges.

The Stable Facade: What the Numbers Say

Coal India’s latest financial performance underscores its continued dominance in the domestic coal sector. With 48% of India’s proven coal reserves under its control and responsibility for 80% of the country’s coal production, CIL operates with entrenched logistical and operational advantages. Its pan-India logistics network, deeply embedded into the country’s energy ecosystem, offers economies of scale few can match.

These factors, combined with a strong balance sheet—₹253,000 crore in consolidated cash reserves—give CIL formidable financial headroom. However, that very dominance is now being tested on multiple fronts.

Under the Surface: Cracks in the Coal Empire

India’s energy sector is undergoing a transformative pivot. While official projections still enshrine coal as a mainstay—the IEA expects coal to meet 68% of India’s power demand by 2026, and the CEA plans to add 80 GW of coal-fired capacity by 2032—the momentum toward renewables is undeniable.

-

- India’s renewable capacity, pegged at 168 GW in 2023, is projected to surge beyond 500 GW by 2030.

-

- Lithium-ion battery prices have plummeted by ~90% since 2010, radically improving the economics of renewables-plus-storage models.

-

- Battery storage requirements are forecast to reach 160 GWh (CEA) or even 600 GWh (NITI Aayog) by 2030, slashing coal’s role in baseload stability.

Simultaneously, captive and commercial coal production is on the rise, empowered by the Mines and Minerals Act, 2021. Private players, now commanding 19% of production, are directly chipping away at CIL’s monopolistic stronghold.

Profit at Risk: Market and Operational Pressures

Global dynamics are exacerbating domestic pressures. Thermal coal prices have crashed from $445/tonne in 2023 to approximately $100 today. While CIL’s domestic pricing structure offers partial insulation, its e-auction premium revenues—a historically lucrative stream—have collapsed from highs of 60% above baseline to below 10%.

Operationally, CIL missed its 1-billion-tonne target again in FY25, producing just 781 mt against a goal of 838 mt, a larger miss than the previous year. Even key subsidiaries like South Eastern Coalfields Ltd underperformed sharply due to land delays, heavy rainfall, and regulatory bottlenecks.

On productivity, CIL lags far behind international benchmarks—less than 1 tonne per man-shift in underground mines, compared with 30-40 tonnes globally.

Diversification: Signals of Intent, But Stumbles in Execution

CIL has publicly embraced the need to diversify. Its initiatives span a joint venture with GAIL for coal-to-gas projects, solar power investments, and even entry into critical minerals with the acquisition of a graphite block in Madhya Pradesh.

These moves, however, remain largely pre-operational:

-

- The graphite mining project is years from production, with no roadmap for downstream value addition.

-

- The 3 GW solar plans, despite being announced in 2020, have yielded little besides a 50 MW operational plant at Nigahi.

-

- The JV with NLC India Ltd, announced in 2018, has made minimal tangible progress in its 3 GW solar and 2 GW thermal ambitions.

This raises questions about the seriousness and pace of Coal India’s diversification—especially when juxtaposed with the urgency of the market transformation underway.

Digging Deeper into Coal: The Path Dependency Risk

Ironically, CIL’s most active capital expenditure is cementing its dependence on coal. Its ₹24,750 crore investment in first-mile connectivity (FMC) projects aims to modernize coal logistics, reducing pollution and increasing efficiency through conveyor-to-rail links. But these long-term projects, stretching into 2027-2029, further embed coal into the energy system.

This deepening investment into fossil infrastructure raises a strategic dilemma: Are such moves locking India—and CIL—into a high-carbon trajectory even as policy and technology push toward decarbonization?

A Narrowing Transformation Window

CIL still holds the cards—cash, assets, and operational dominance—to engineer a successful pivot. But time is fast running out. As private miners expand, renewables scale up, and storage becomes cheaper, the margins for error are shrinking.

The real question is no longer whether coal will remain relevant in India’s energy mix—it undoubtedly will in the medium term. Instead, it is whether Coal India can evolve quickly enough to remain a pivotal player in a radically restructured energy landscape.

If the company continues to over-invest in coal and underperform in diversification, it may soon find itself in a position it has never experienced before: playing catch-up in the very sector it once defined.

Conclusion:

Coal India’s FY25 performance might reassure shareholders in the short run, but the writing on the wall is clear. Unless it accelerates its transition efforts with strategic coherence and execution discipline, its present profits could become tomorrow’s stranded assets. The energy future will still include coal—but whether it will include Coal India as a central player remains an open question.